In the 1890’s Western Australia’s wool industry attracted Afghan camel drivers and they contributed much to the prosperity of Australia. When, in the 1920’s and 1930’s trucks started transporting wool, the camels were set free and the Afghans took up new occupations.

Once, as I walked through the city on a sunny spring day, I passed a green door in the high white wall abutting the pavement. I stopped, opened the door and entered the compound. A small white-washed mosque, with several arabesque arches, was centrally located, complete with facilities for ablutions for ritual purification.

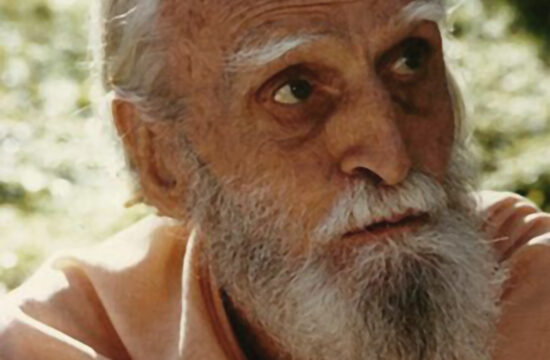

I found the elderly, slightly-built caretaker of the mosque. His name was Iset Khan. He invited me to join him for tea where he lived — in the little room in the backyard of the mosque. He didn’t use electric lights and so used a kerosene lamp. Having brewed the tea on a small gas stove, he served it with unassuming friendliness in a battered tin mug. He offered a very old chunk of fruitcake which I dunked in the tea. He was, I sensed, a sincere and good man.

He said, “The few Afghans left in the community, those descended from the camel-drivers of the last century, asked me to lead them in Friday Prayer. I’m also the caretaker. In return they allow me to live here. As you see, I live in safety and comfort.” I said that in my experience very few people live so simply, to which he responded: “If I do not live life in a simple way, things will get complicated and I will create a web of frivolous goals that lead me toward the chains of materialism.” I nodded agreement. He continued, “My focus, if not simple, would shift from a God-oriented life to a Godless, material existence. Prophet Muhammad once predicted that material wealth will be the cause of much evil amongst the people of the latter times.”

I admired his quiet, contentment, his simple lifestyle, and service to the small community of Afghans who came for Friday prayers. Iset explained how, through his own example, he supported and practiced the central five observances of their faith: “These are giving witness to my faith, ritual prayer five times daily, giving alms to the poor even though I have very little myself, fasting during the month of Ramadan, and pilgrimage, if possible, to the city of Mecca.”

He then explained his daily spiritual practices. “First I ritually wash, cleansing both mind and body. I wash my hands, arms, face, neck, and feet. My prayers are performed facing the direction of Mecca. Of course, praying together is preferred to solitary prayer. So while I pray with all on Fridays, I pray alone here on other days.”

The old man was the first really impressive human being I had met beyond my family, who practiced a profound simplicity of life. He exemplified spirituality with integrity. Yes, he observed all the practices of his faith, and his faith impels him to brew and graciously offer a cup of tea, be courteous and hospitable to a stranger, and sincerely share the wisdom of a lifetime. His was a faith hidden under the mask of the ordinary and the humble. On parting, Iset Khan gave me a small card. It had a line from the mystic poet Rumi. It read, “Do not feel lonely, the entire universe is inside you.”

Was he trying to explain his life lived all alone? Was it a nudge to me too? When we hold the entire universe inside us, why should we ever feel lonely?

Rev. Dr. Meath Conlan is a Counsellor and Adult Educator. He travels frequently to India. He can be contacted at [email protected]