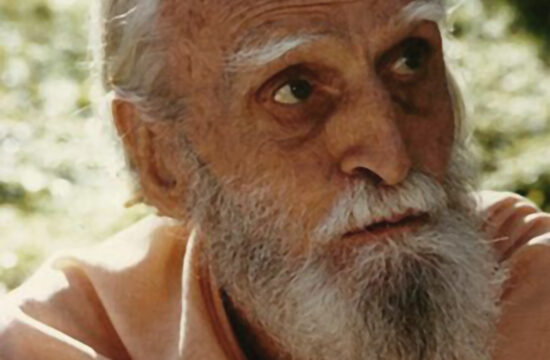

Khejok Tulku Rinpoche was one of the diminishing numbers of “old teachers” in the Tibetan tradition. Born in the 1930s, he was installed as Abbot of the second oldest monastery, Dhe Tsang, in Eastern Tibet. Later, while trying to escape to India, Rinpoche was arrested and imprisoned by the Communists.

Despite two years of hard labour, Rinpoche maintained his daily spiritual practices. He helped many fellow inmates spiritually and medically. Eventually a guard helped him escape from prison. Rinpoche crossed the Himalayas, and finally arrived in Australia in 1986.

I met Rinpoche soon after his arrival and we were firm friends until his death in 2013. I thrice accompanied him to his monastery in Tibet. I observed his daily practices of meditation, chanting and prayers. Many sought his advice which he cautioned was beneficial, only if one practiced it: “My advice must be etched into your heart – not merely as words recalled by the mind. Then your actions, thoughts, and speech will reflect those qualities of which I speak and practice. Even unconsciously, every single word you utter, every gesture you make, will be your teaching to the world, and the world will benefit, just by your mere presence.”

Rinpoche taught the Dharma with unfailing humility and serenity. All who sought his advice wanted inner peace, though, reflecting with me once, he found it curious how people talk about finding peace of mind: “Peace of mind has always been there. One only has to realize it. People go to all sorts of places to find peace of mind. If you do not have it within yourself, you can go to the end of the world but you’ll never find it.”

I always found him eminently practical and grounded. His advice was often tinged with good humour. He once talked about happiness: “The key to a happy life is to be grateful for everything. Sickness gives you the opportunity to appreciate health. Problems give you challenges to find solutions. Loneliness gives you time to reflect. Company gives you teachers to learn from. Failures also give you lessons to learn. Andold age brings wisdom!”

While teaching meditation, he drew on his own lifelong practice. Showing me his bent fingers, he shared with me something of his years in the Chinese prison, where guards broke every finger in his hands. He said: “People can torture you; they can insult you; they can take away all you have; they can put you in the darkest prison and starve you. If you are determined to be happy anyway, no one can take that smile off your face.” With kindness and patience, he made friends with his guards. Reflecting on this he told me: “A hostile person is your teacher of tolerance: rejoice when you meet one. It is not every day that you have the perfect opportunity to practice your patience.”

In 1987 I took Rinpoche to the Benedictine monastery near Perth, Australia. Remarkably every monk attended his talk-demonstration of meditation, following his instructions exactly. Somehow they recognised an authentic, deeply joyous human being. I shared my astonishment with him over the full attendance. He remarked, “Happiness is like a lamp. When a lamp is lit, it does not need to say to the dark corners of the room, “Let me illuminate you and dispel your darkness,” or make any other effort to make the room bright. The dark corners of the room simply become bright as soon as the light is lit. When your life is filled with happiness, the lives of those around you will be also brightened, without you needing to do anything.”

Rev. Dr. Meath Conlan is a Counsellor and Adult Educator. He travels frequently to India. He can be contacted at meathconlan@icloud.com