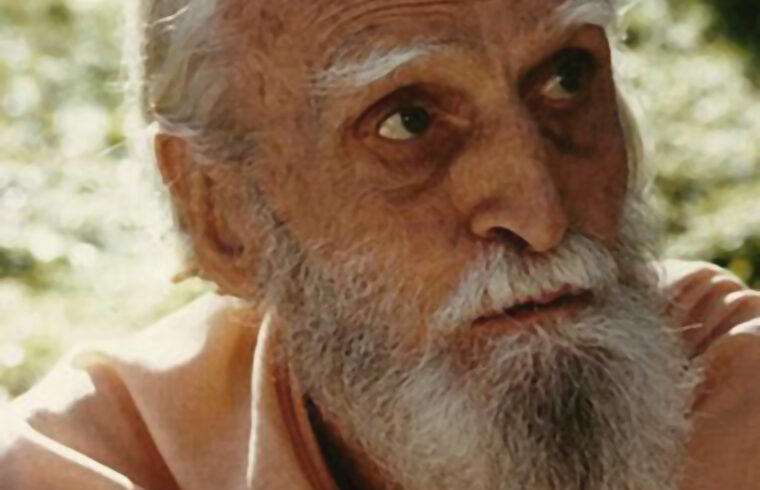

Once I turned for guidance to the late Dom Bede Griffiths, a British Benedictine monk, who lived for many years and died at Shantivanam, also called Saccidananda Ashram, near Kulithalai in Tamil Nadu, India. As a young man he had an experience of Nature that left him with a “feeling of awe,” such that even the sky seemed “but a veil before the face of God.”

Subsequently, the smallest details of nature drew him beyond himself, to the awareness: “We are no longer isolated individuals in conflict with our surroundings; we are parts of a whole, elements in a universal harmony,” he said.

On my visits, I saw him daily sitting in his garden outside his hut at Saccidananda Ashram. He said he created this colourful space “because a garden provides spiritual opportunities for breaking the daily routine and of quiet listening. A garden is God’s message bearer to the soul, as though a veil has been lifted.”

When, sometimes, he felt cut off and isolated from the world, Fr Bede said: “I sought ways of discovering a sense of unity and meaning in my day-to-day experiences. I would stop, and listen, watch and learn.” Based on his own experience, he recommended: “When you are thrown back on self-doubt and confusion, live in the light of all you observe and feel part of it; shape your life by its law.”

But it doesn’t come cheaply, he said. “It calls for all our energies, and involves both labour and sacrifice; each one approaches it from a different angle and has to work out his own particular problem. I find meditation, prayer, spiritual reading and the daily Eucharist are the cornerstones of my day.”

Some days around 2.30 AM, I would see him sitting deep in contemplation, which was his unfailing daily preparation for the Eucharist, the celebration of which was enhanced by his intoning Sanskrit chants and Tamil songs, and adapting several Indian rituals such as waving of lights, scattering water and placing of flowers around the bread and wine.

When I sought a reliable way of contemplation, Bede Griffiths urged me to try what he had been using for years: “I strongly urge you to use the method I do – I call it ‘Jesu-Abba’ meditation.” His instruction was simple: “Sit comfortably, relax, attend to your breathing. As you inhale quietly say ‘Jesu.’ On exhaling quietly say ‘Abba’. Keep going like this for twenty or thirty minutes twice a day – or more if you can.”

Bede Griffiths’ spiritual journey began in his youth with a spiritual experience of nature, where “every step in advance is a return to the beginning.” It finally led him to seeing Cosmic beauty everywhere, “which is truth and Love, for the divine is found, not only in Nature, but also in the minds and hearts of human beings.”

Reminiscing on his life, he said: “I sought the divine in the solitude of nature, and in the labour of my mind.” But eventually he found God in his community and the spirit of charity. Until then he felt he had been “wandering in a far country and now had returned home,” that he “had been dead and was alive again;” that he “had been lost and was found.”

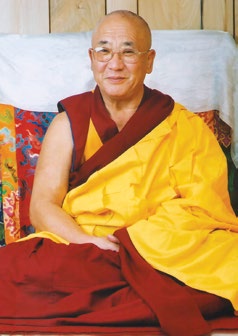

Here in Australia and many parts of Europe, churches are empty. But the ordinary people seek new ways of thriving spiritually. Once I heard Fr Bede share with the Dalai Lama: “It is likely, because of the Tibetan diaspora, many Catholic Christians will find the roots of their own rich tradition of meditation.” His words have come true. Many Christians have now discovered that what they thought were new ways of praying and meditating have indeed been ancient practices of Christian contemplation from the time of Desert Fathers and Mothers.

Rev. Dr. Meath Conlan is a Counsellor and Adult Educator. He travels frequently to India. He can be contacted at meathconlan@icloud.com